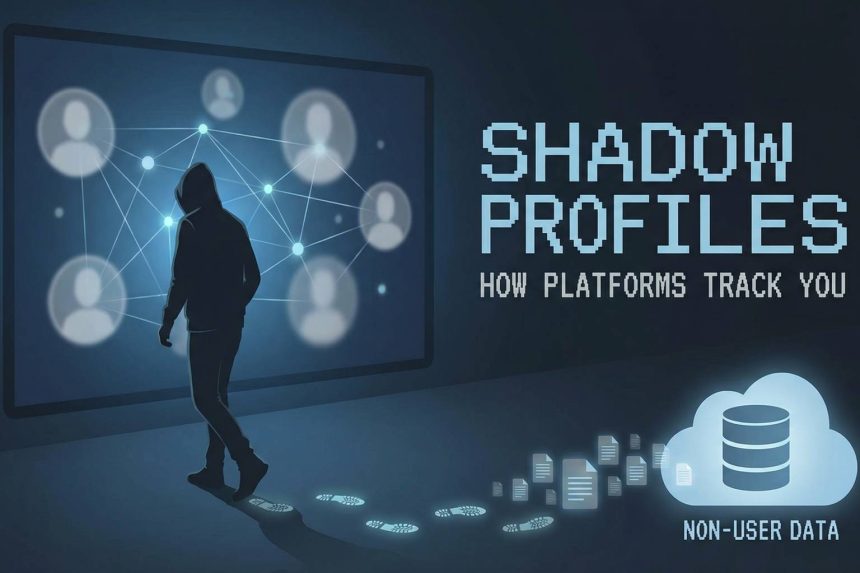

You close your account. You uninstall the app. Maybe you never even signed up in the first place.

It feels like you have stepped out of the system.

But in reality, many platforms haven’t stopped tracking you — they have simply moved you into a different category:

the invisible world of shadow profiles.

- What exactly is a shadow profile?

- How platforms build profiles for people who never signed up

- 1. Contact list uploads

- 2. Web trackers and cookies

- 3. Matching emails and phone numbers from leaked or purchased data

- 4. “People you may know” and social graph inference

- Why shadow profiles matter — even if you “have nothing to hide”

- Targeting the unregistered: advertising and influence without accounts

- Data rights vs. data reality

- Why platforms don’t want to give up shadow data

- How this connects back to the Cambridge Analytica era

- What you can do — and where the limits are

- Rethinking consent in a networked world

- Living with the invisible copies of ourselves

A shadow profile is a collection of data about you, built and maintained by a platform,

even if you are not an active user — or never were.

It is data stitched together from your contacts, your browsing patterns, your devices, and your social graph.

You may never see it, but it can still be used to identify, target, and categorize you.

What exactly is a shadow profile?

A shadow profile is not necessarily a formal “account” in a traditional sense.

It is more like a hidden dossier built from:

- Contact lists uploaded by other users

- Cookies and trackers embedded across the web

- Device identifiers shared between apps and services

- Location data collected by third-party SDKs

- Purchase and browsing data from advertising networks

Even if you have never clicked “Sign up,” your phone number, email address, name, and relationships

can end up in a platform’s internal database because your friends, family, or coworkers did.

In other words: you don’t need to be online to be part of the online data economy.

How platforms build profiles for people who never signed up

There are several ways companies can assemble detailed views of non-users or former users.

1. Contact list uploads

Many apps — messaging tools, social networks, payment apps, ride-sharing platforms — request access to

your phone contacts “to help you find friends.”

When users agree, they often upload:

- Phone numbers

- Email addresses

- Names and nicknames

- Sometimes notes or labels (e.g., “HR Manager,” “Landlord,” “Therapist”)

This means that someone who never installed the app can still appear in the platform’s internal database.

The system may not call it an “account,” but functionally, it is a record connecting identifiers (like a number

or email) to a network of relationships.

2. Web trackers and cookies

Even without an account, you may encounter:

- Tracking pixels

- Third-party cookies

- Fingerprinting scripts

- Analytics SDKs in mobile apps

These tools can:

- Log your IP address and device type

- Record which pages you visited and when

- Associate your browser with specific interest categories

- Connect visits across different websites and apps

When combined with other data sources, they help platforms infer who you are, what you like,

and how to reach you — even if they do not yet know your name.

3. Matching emails and phone numbers from leaked or purchased data

Data does not stay isolated.

It moves through:

- Data brokers

- Marketing agencies

- Third-party audiences sold to advertisers

- Leaked or breached databases circulating on the web

When a platform acquires additional datasets — legally or otherwise — it can match them with existing

identifiers like emails, phone numbers, or device IDs to enrich shadow profiles further.

4. “People you may know” and social graph inference

If a platform sees that several registered users share your phone number or email in their contact lists,

it can infer:

- Who you are likely connected to

- Where you might live or work

- Which communities you belong to

Later, if you ever sign up, the platform can instantly suggest a network of contacts —

because from its perspective, you were never truly “outside” the system.

Why shadow profiles matter — even if you “have nothing to hide”

Some people shrug off this practice, thinking: “I’m not a public figure. Who cares if they have my data?”

But shadow profiles raise serious concerns:

- No transparency – you cannot view, edit, or correct data that is collected behind your back.

- No consent – you never agreed to be tracked, yet you are.

- Network exposure – your relationships and associations are mapped without your knowledge.

- Future risk – data collected today can be reused or misused tomorrow in ways nobody anticipates.

When Cambridge Analytica used psychographic profiling, it relied on data from people who never knowingly

chose to be part of a political experiment.

Shadow profiles extend that logic: you can be profiled, targeted, or influenced even without explicit participation.

Targeting the unregistered: advertising and influence without accounts

Shadow profiles are not just an internal curiosity.

They have real-world consequences, especially in advertising and political communication.

Through combinations of:

- Device IDs

- Hashed emails

- Phone numbers

- IP-based household targeting

platforms and ad networks can:

- Deliver personalized ads to devices that are not linked to any visible account

- Include non-users in “lookalike audiences” based on similar behavior

- Track responses and refine models even without a login

In political contexts, this means that messaging strategies can reach far beyond those who intentionally

follow a candidate or party.

Influence spills over into the shadows — into the lives of people who never consciously opted into a campaign.

Data rights vs. data reality

On paper, privacy laws like the EU’s GDPR grant rights such as:

- The right of access (knowing what data is stored about you)

- The right to rectification (correcting errors)

- The right to erasure (the “right to be forgotten”)

In practice, these rights are difficult to exercise against shadow profiles because:

- You may not know the profile exists

- The platform may not classify it as “personal data” attached to a user

- Technical systems may not be designed to expose or delete such records on request

Some companies argue that data tied only to hashed identifiers or device IDs is “pseudonymous”

rather than fully personal — despite the fact that it can be linked back to individuals when needed.

Why platforms don’t want to give up shadow data

From a business perspective, shadow profiles are extremely valuable because they:

- Help platforms grow faster by recommending relevant connections to new users

- Expand ad targeting reach beyond their active user base

- Increase the precision of analytics and audience insights

- Provide continuity when people delete accounts and later return

And because shadow data is largely invisible to the public, it attracts less scrutiny than

front-facing features.

The incentives are heavily tilted toward collection, not restraint.

How this connects back to the Cambridge Analytica era

The Cambridge Analytica scandal highlighted how data from one group of people could be used to infer and

influence another group that never gave meaningful consent.

Shadow profiles continue this pattern:

- Your friend grants an app permission; you become indirectly mapped.

- Your coworker uploads a contact list; your work number enters a database.

- Your browsing is tracked by ad pixels; your interests are modeled in the background.

It is a network effect of surveillance: the choices of people around you can pull you into

systems of profiling, whether you participate or not.

What you can do — and where the limits are

Completely avoiding shadow profiling is almost impossible in a connected world,

but you can still reduce your exposure.

- Encourage friends and family to be cautious with contact uploads.

- Disable automatic contact sync in messaging and social apps where possible.

- Use browsers and extensions that block third-party trackers and fingerprinting scripts.

- Regularly reset advertising IDs on your phone (where supported).

- Use email aliases and separate addresses for sensitive services.

On the legal front, in some jurisdictions you can:

- Send data access requests to companies, even as a non-user, using known identifiers.

- File complaints with data protection authorities if you suspect unlawful profiling.

However, the structural problem remains: shadow profiles are designed to be hidden.

Rethinking consent in a networked world

Shadow profiles expose a fundamental flaw in traditional ideas of consent.

The classic model assumes:

- Individuals decide when to share data

- They understand what they are agreeing to

- Their choices affect only their own privacy

In reality:

- Other people’s choices expose your data

- Complex tracking systems operate beyond human comprehension

- Profiles are built even in the absence of explicit consent

As long as entire business models depend on maximum data extraction, shadow profiles will continue

to exist — and expand.

Living with the invisible copies of ourselves

Shadow profiles are a reminder that in the digital age, there is often a gap between how we experience

the internet and how it actually works.

You may feel disconnected from a platform, but somewhere in its infrastructure, a quiet reflection

of you remains: partial, probabilistic, but powerful enough to influence how you are seen and targeted.

Understanding that these hidden profiles exist does not solve the problem.

But it changes the story from “I’m not on that platform, so I’m safe” to a more realistic question:

Who is building a version of me in the background — and what are they doing with it?